Introduction

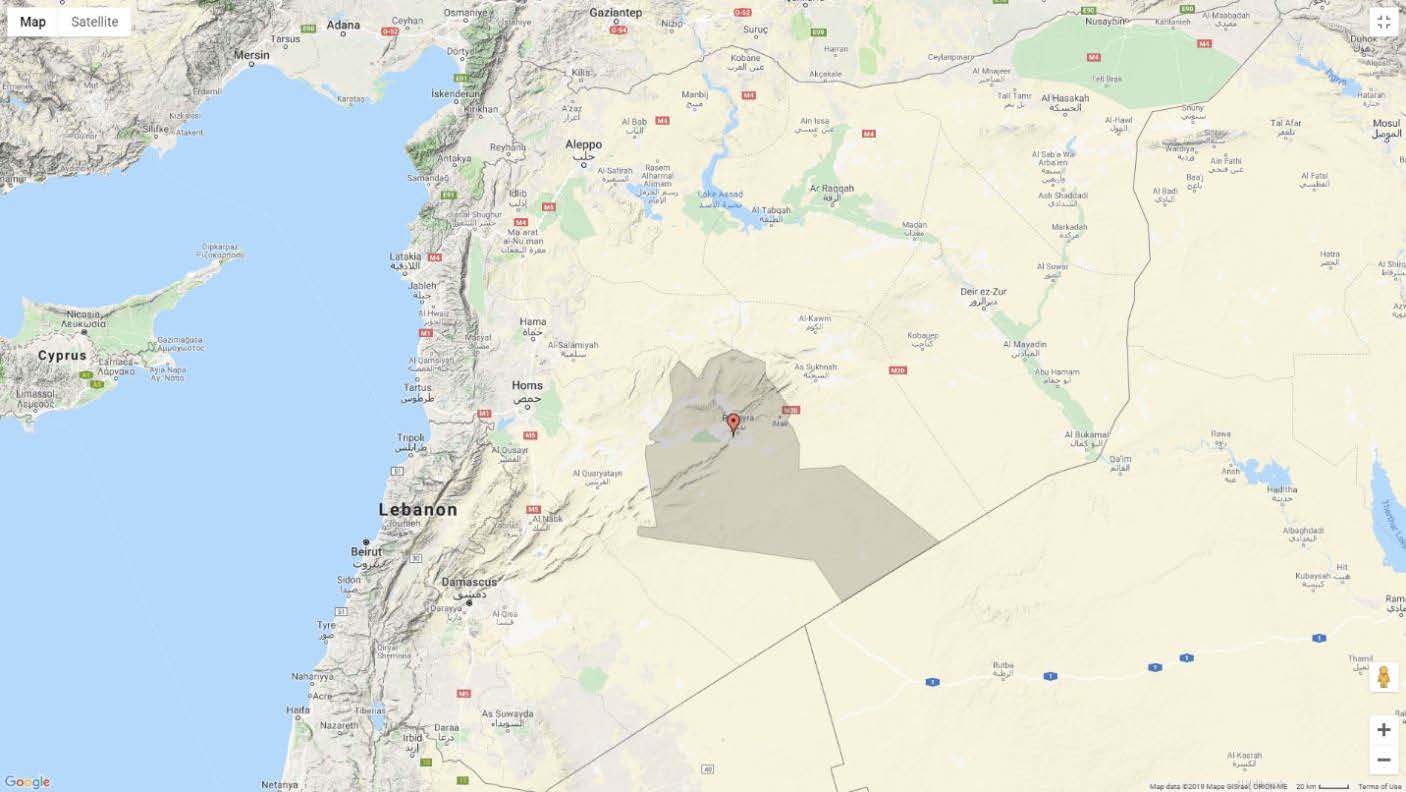

The renowned city of Palmyra, characterized by its semi-desert climate, is located in Syria, 240 kilometers northeast of Damascus and 160 kilometers from the city of Homs, to which it is administratively affiliated (Figure No. 1). Numerous writings indicate that one of the Amorite tribes established a small settlement in Palmyra during the third millennium BCE. However, the city did not gain its fame until the fourth century BCE, when it flourished under the leadership of a major Arab tribe and became a hub for trade routes connecting Antioch to Babylon. The peak era of power and prosperity for Palmyra spanned the first three centuries CE, during which it became the largest commercial center in the East. Palmyrene merchants travelled globally, as evidenced by archaeological discoveries such as Palmyrene coins found in England and inscriptions from Hadramaut and Socotra in Yemen. During this period, most of Palmyra’s buildings were constructed, showcasing its immense heritage, its monuments reflecting luxury and grandeur. King Odaenathus and later his wife Zenobia attempted to establish an empire, but their efforts ended with Zenobia’s defeat by Roman Emperor Aurelian in 273 CE. In subsequent eras, there were local attempts to revive Palmyra, the most notable being during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian, and another by Prince Hassan ibn Bahdal al-Kalbi during the Umayyad period. However, these did not endure. Palmyra continued to be mentioned throughout history by many Arab historians and travellers, such as Yaqut al-Hamawi in his book Mu’jam al-Buldan and Ibn Nazif al-Hamawi in his book Al-Tarikh al-Mansuri. The first Western travellers to reach Palmyra and describe its ruins were Della Valle (between 1616 and 1625) and Tavernier (in 1638). Later, Robert Wood visited Palmyra in 1751 CE and noted that there were 30 houses inside the Great Temple (Temple of Bel) in Palmyra.

Palmyra was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1980 due to its well-preserved Roman ruins, before its destruction in 2015. Palmyra holds significant symbolic value for the Syrian people, as it is part of their living memory and a source of pride.

The former Syrian regime sought to exploit Palmyra’s antiquities to achieve political gains, ignoring the damage inflicted on the city’s cultural heritage. In this context, the initiative Palmyrene Voices continues to document the violations and crimes of the former regime, not only against cultural heritage but also against the residents of Palmyra, whose current population exceeds 100,000. These residents were displaced by Assad and ISIS, resulting in their forced migration due to the inhumane treatment and punishment they suffered. This report provides a field-based evaluation by the Palmyrene Voices team for the first time after 10 years of diaspora and remote work. It presents the painful reality of Palmyra and its residents, once known as the “Bride of the Desert.”

- A Historical Sequence of Illegal Excavations and Looting of Palmyrene Artifacts Until 2015

Archaeological excavations in Palmyra began during the 1860s under Ottoman rule. Despite the existence of a law prohibiting the export of cultural heritage without permission, traders and artifact collectors competed to acquire Palmyrene pieces.

In 1899, Russian Prince Lazarev obtained Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s approval to transfer Palmyrene artifacts to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, while the Danish consul took a rare collection of Palmyrene sculptures to the Ny Carlsberg Museum in Copenhagen. At that time, excavations were unmethodical, overturning sites and archaeological layers, focusing only on large sculptures and significant artifacts.

Although excavations later became systematic and scientific, the French contributed significantly to transferring funerary sculptures and Palmyrene artifacts to the Louvre and other European museums. In 1920, the French Mandate government issued an antiquities law in Syria based on French law, regulating archaeological missions, although the trade in antiquities was still permitted. This law remained in effect until the mid-1950s when antiquities trade was banned, and the current Syrian Antiquities Law was enacted in 1963.

In the early years after independence from the French Mandate, Syrians became aware of the need to prevent the trade of their heritage. However, with the advent of the Assad regime, both father and son, the situation changed, and many influential figures dared to engage in the trade of antiquities and the looting of archaeological sites in search of treasures and valuable artifacts. During this period, numerous foreign archaeological expeditions were allowed to work in Palmyra, including German, Swiss, French, Polish, and Italian teams, alongside local missions.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in March 2011, Palmyra’s antiquities became increasingly vulnerable to looting and destruction. The city experienced a breakdown of security and widespread chaos, and during this time many opportunists, supported by regime loyalists, engaged in random excavations in search of artifacts and treasures.–

In early 2013, a local opposition group took control of Palmyra’s oasis and parts of the eastern city. According to reports from the Palmyra Antiquities Directorate on the general state of the archaeological site, “some of these individuals contributed to illegal excavation activities.” Additionally, rockets and shells from Assad’s forces at that time caused significant damage to the oasis, several tombs, parts of the walls of the Temple of Bel, the house with Greek mosaics east of the Temple of Bel, and sections of the eastern and southern walls surrounding the city. Assad’s forces continued their violations in Palmyra, particularly by constructing numerous roads through the oasis and archaeological site, cutting through its historical monuments under the pretext of protecting the city.

Palmyra’s Antiquities Between the Hammer of ISIS and the Anvil of Assad

Prior to the invasion by the Islamic State (ISIS), and according to testimonies from some employees of the Palmyra Antiquities Directorate, specifically on April 1, 2015, Syrian authorities instructed the Palmyra Antiquities Directorate to prepare rare and valuable artifacts registered in the Palmyra Museum. This was accomplished within days. However, the Syrian authorities did not order their transfer until the final hours before ISIS entered the heart of the city, specifically at 9:00 AM on Wednesday, May 19. Following a truce between the two conflicting parties, some of these artifacts were transported to Damascus via a dump truck belonging to the Palmyra Museum, while the majority were left to their fate with ISIS fighters, who proceeded to destroy what they could reach in the Palmyra Museum.

On 19 May 2015, after battles whose seriousness locals questioned with Assad’s forces ISIS took control of Palmyra. Assad’s forces regained control of the city with Russian and Iranian support in March 2016, only for ISIS to retake it in December of that same year. ISIS was finally expelled from Palmyra in March 2017, leaving it once again under Assad and his allies’ control.

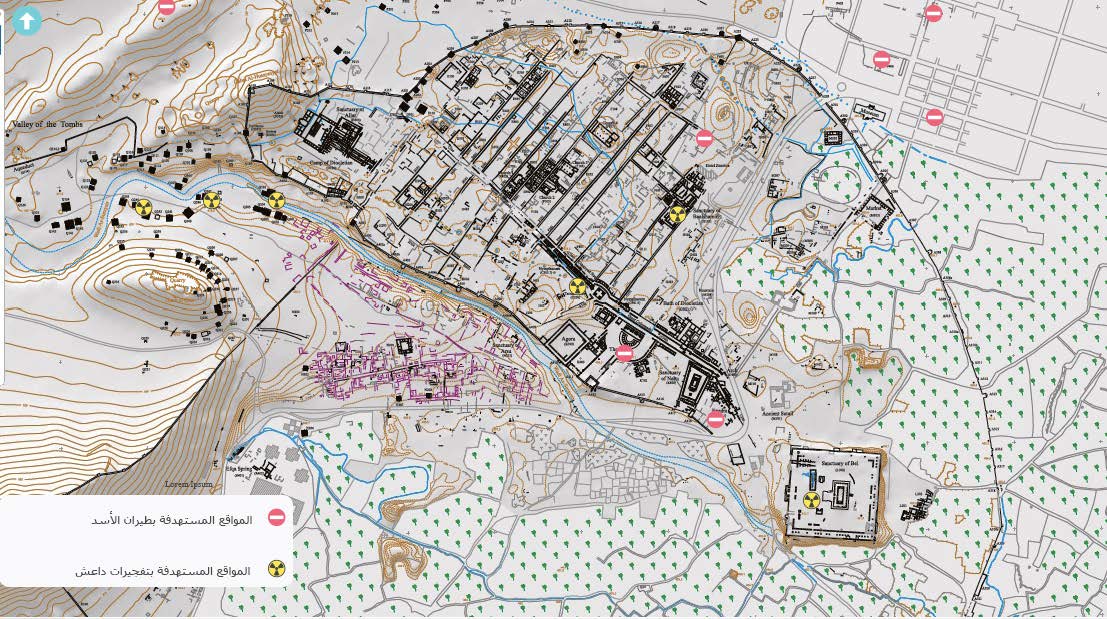

During ISIS’s invasion, its fighters destroyed many artifacts in the Palmyra Museum and placed explosives in archaeological buildings. This caused severe damage to the Temple of Baalshamin, the Temple of Bel, the Tetrapylon, and the tower tombs, house tombs, and underground tombs. The Arch of Triumph was bombed by airstrikes from Assad’s forces and their Russian allies, which caused its stones to fall without disintegrating, unlike other buildings destroyed by explosives. The airstrikes also targeted and partially destroyed the roof of the city museum building. Additionally, they bombed and damaged the entrance to Palmyra Castle overlooking the archaeological city. The Palmyra Theater was used by ISIS fighters to film execution scenes (Figure No. 2).

The greatest catastrophe resulting from ISIS’s invasion of Palmyra was the total displacement of its population, which exceeded 80,000 at that time. This displacement was caused by ISIS’s inhumane treatment and punishment of residents, along with continuous shelling by Syrian regime forces attempting to regain control of the city. During those moments, residents faced death, and their only chance for survival was to flee.

The survivors of the conflict fled to cities controlled by the Assad regime, such as Homs and Damascus, as well as cities under Syrian opposition control, including Idlib, Maarrat Misrin, Kafr Daryan, Dana, Al-Bab, and Manbij, among others. Some of the displaced Palmyrenes managed to reach Jordan in the south, while others crossed the Turkish border and settled in Turkish cities like Hatay, Gaziantep, Mersin, and Istanbul. A number of them continued their journey to European countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Because of the dispersal of the diaspora, it has become difficult to bring all these people together in one place or on one platform.

The heinous crimes committed by ISIS in Palmyra generated widespread international sympathy for the city. The Assad regime exploited this sentiment in an attempt to enhance its image and present itself as the savior of Palmyra’s antiquities. Many countries and entities praised this achievement, overlooking Assad’s crimes against Syria’s heritage. The regime quickly announced its intention to rehabilitate and restore the archaeological city of Palmyra. This announcement was endorsed by its Russian ally, leading to the signing of several restoration projects with Russian entities such as the Hermitage Museum and the Russian Academy of Sciences. One notable project was the restoration of the Arch of Triumph, planned in three phases in collaboration with the Syrian Trust for Development and the Syrian Ministry of Culture. The first two phases—sorting and documenting stones and preparing blueprints—were completed. However, initiating the final phase of rebuilding the arch, scheduled for December 2024 according to the director of the Center for Rescue Archaeology at the Russian Academy of Sciences, was delayed due to the victory of Syrian opposition forces and the fall of Assad’s regime.

Additionally, there was a Syrian-Russian partnership to restore the façade of Palmyra’s theater, involving rubble management and documenting its current state. The historical Afqa spring was restored by Syria’s Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums in collaboration with Russia’s Society for Historical and Cultural Heritage Preservation. Furthermore, an agreement was signed between the Hermitage Museum and Oman’s National Museum to restore 200 Syrian artifacts, including Palmyrene sculptures.

Separately from Russian efforts, a European-Polish-funded restoration project focused on repairing the Lion of Al-lāt statue damaged in 2015 during ISIS control. The statue’s pieces were transferred to Damascus Museum in 2017 and displayed in its garden.

The Current Reality in Palmyra After Liberation and the Fall of the Assad Regime

On December 8, 2024, Syria achieved freedom with the fall of the Assad regime, which had both positive and negative impacts on the future of archaeological sites, particularly Palmyra. On the negative side, the resulting security vacuum increased the risk of looting and vandalism, necessitating intensified efforts by the current administration to protect the archaeological site. Conversely, the change in leadership marked the end of a corrupt era, potentially facilitating the protection, reconstruction, and restoration of Palmyra’s heritage and its reestablishment as a tourist destination in Syria. During a field visit by a member of the Palmyrene Voices initiative, “Mohammed Fares,” on January 5, 2025, initial observations were made to assess the current state of the site:

- Residents and the Residential City (Az-Zahera City)

In 2015 and 2016, Palmyra experienced intense bombardment by warplanes belonging to Assad’s forces and their allies under the pretext of targeting ISIS. This resulted in near-total destruction of the city. Many buildings were reduced to rubble, while others sustained partial damage, forcing residents to evacuate immediately. In 2015, all Palmyra residents were compelled to flee to other cities or countries.

The journalist and writer Mohammed Al-Abdullah, a native of Palmyra, stated to Al Jazeera that “the residents of the city, which Syrians fondly call the ‘Bride of the Desert,’ were forcibly displaced from their homes due to continuous aerial bombardment. The city became almost devoid of inhabitants after those who remained and those who had previously sought refuge there fled toward the desert, where they now live in extremely harsh conditions.”

Journalist Mohammed Idris described the destruction in Palmyra’s neighborhoods: “The regime and ISIS turned it into hills of rubble, ghostly residences, and more recently military barracks for Iranian forces since 2016. A large number of homes are destroyed, the streets are empty, and the city’s neighborhoods look like ghost towns.”

After the fall of Assad on December 8, 2024, hundreds of displaced families began returning to their city, Palmyra. The current situation of the residential city and its population is described by Mohammed Fares, a volunteer with the Palmyrene Voices initiative: “The state is extremely dire. Estimates suggest that 80% of the buildings are either destroyed or at risk of collapse. Remnants of weapons and landmines are still scattered everywhere; just today, two people were killed by a landmine explosion in the northern neighborhood. So far, no security forces from the current administration have entered to protect the city or organize residents’ affairs.

On another front, basic services such as water, electricity, internet, education, and healthcare are almost non-existent. The population suffers from severe poverty; many cannot secure their basic needs. Around 10,000 people have returned—approximately 10% of Palmyra’s total population of 100,000. Efforts are underway by locals to facilitate the return of families from Rukban Desert Camp; so far, only 60 out of 1,500 families have been brought back. There are no job opportunities for these returnees, who rely on modest aid from expatriates to secure food and water. They use primitive tools to clear debris blocking access to what remains of their homes. Healthcare services are absent; while there is a hospital building, it lacks staff and equipment. Recently, an elementary school and a middle school were opened with very limited resources.

Despite these harsh conditions, I am optimistic about the future of heritage preservation based on discussions among locals. They affirm their determination to protect the antiquities and museum and prevent anyone from tampering with their heritage with individual attempts to looting and secret excavations.”

Amid these tragic circumstances and significant challenges, many residents continue to say: “A devastated homeland is better than the oppression of exile.” (Figure 3)

- The Oasis

The oasis has long been the primary lifeline for Palmyra’s residents, both in the past and present, characterized by its orchards enclosed by mudbrick walls. The oasis relies on irrigation from the Efqa spring, with part of it also watered by the canal spring extending from Abu al-Fawaris, 7 kilometers west of Palmyra. Every resident of Palmyra holds cherished memories of the oasis; the elderly recall the joy of drinking tea boiled over wood fires after a day of gardening, while women remember the pleasant times spent with family or friends in the orchards. These memories have become part of the past for Palmyrenes, who were displaced to distant lands after May 2015. Their suffering was exacerbated by the fires on May 25, 2020, which burned nearly half of their 400-hectare oasis, particularly in its western section. These fires were set by the Assad regime, depriving local people of their “lifeline”. All they could do was share photos and videos of the flames as they watched in anguish while the last element of Palmyra’s beautiful desert trilogy was destroyed (In addition to the population and archaeological site), unable to escape the tragedy of the Syrian conflict.

In addition to the burned section, the remaining trees in parts of the oasis that no longer receive spring water have dried up and turned into deadwood. Currently, some orchard owners who have returned from displacement are using simple means to save what remains of their palm and olive trees. (Figure 4)

- Palmyra Archaeological Museum

According to the field survey, the museum garden contains numerous heavy statues and funerary beds, most of which are shattered or broken, while some remain in good condition. The structural integrity of the museum has been compromised by aerial bombardment, resulting in holes in the roof that have been temporarily sealed with metal sheets. The current exhibits consist of broken pieces, with some artifacts having been transferred to the Damascus Museum prior to ISIS’s takeover and not yet returned. The museum is currently not operational, but guards from the Directorate of Antiquities and some local volunteers are protecting it without support from the new administration, despite the pressing need for such assistance. Additionally, there is no administrative staff overseeing the museum at present. (Figure 5)

- Palmyra Castle (The Ayyubid Castle)

The castle’s walls were damaged, and parts of its upper towers, particularly on the northern, eastern, and southern sides, collapsed due to airstrikes during ISIS’s control of the city in 2015. Access to the interior of the castle is difficult because of collapses at the entrance. Evidence of military positioning was found, including thick sand berms and some block buildings equipped with artillery that were abandoned by Assad’s forces during their retreat. (Figure 6)

- The Archaeological Site /the Ancient City/

1) Temple of Baalshamin

The temple was destroyed by ISIS on August 23, 2015, turning it into rubble and ash. No significant documentation or restoration efforts have been conducted at the site . A theoretical study titled “The Temple of Baalshamin: A Workshop on Palmyra’s Vision After Liberation,” supervised by Dr. Abeer Arqawi, was conducted to document the temple’s history, describe its architectural elements and artifacts. and identify the missions that worked on the building since its discovery. (Figure 7)

2) Temple of Bel

The sanctuary of the Temple of Bel was destroyed by ISIS on August 30, 2015, reducing it and the surrounding colonnade columns to rubble. Only the entrance supports to the cella remain, while the temple’s outer walls are relatively intact, albeit with some damage to their columns, stones, and decorative elements.

In 2016, the Russian Academy of Sciences attempted to create a digital 3D model of the temple as a preliminary step toward its future reconstruction . (Figure 8)

- Arch of Triumph and the Grand Colonnade

A narrative circulated among local residents on October 4, claiming that ISIS militants had blown up the Arch of Triumph and three columns along the Grand Colonnade connecting the Arch to the Tetrapylon. However, a field inspection of the fallen stone pieces from the Arch does not indicate an explosion. It is more likely that the stones fell due to an airstrike nearby.

Additionally, sorting and numbering of the fallen pieces from the Arch of Triumph was observed, likely conducted by Russian entities in preparation for restoration efforts. Meanwhile, illegal excavation activities were noted along the Grand Colonnade, which were not present before 2015) Figures 9, 10(.

4) The Tetrapylon

Field inspections of the four structures, known as the Tetrapylon, revealed that they were subjected to explosions, reducing their columns to a pile of rubble and scattered stone fragments. There are no indications of any documentation or numbering of the stones (Figure No. 11).

5) The Theater

On July 3, 2015, ISIS carried out a mass execution inside Palmyra’s archaeological theatre, claiming that the victims were members of Assad’s forces. Field inspections of the Theater revealed a collapse in its façade (the upper section of the orchestra). The large fallen stone blocks do not indicate the use of TNT, which ISIS commonly used to destroy Palmyra’s landmarks. Instead, it is likely that the damage resulted from a missile strike. Joint Syrian-Russian efforts were made to restore the façade of Palmyra’s Theater. A digital 3D model of the Theater was created, and sorting and numbering of the fallen stones were conducted in preparation for restoration. (Figure 12)

6) Western Fortifications and the Camp of Diocletian

At the top of the hill known as “Jabal al-Husayniyat,” a recently abandoned military position was found. However, the more significant issue is the presence of extensive clandestine excavations at the site of the Camp of Diocletian. A relatively large area appears to have been manually excavated, exposing architectural remains, including stone foundations and fragments with various decorations from funerary beds and some funerary busts. What raises questions is that the excavation site is located near the military fortifications of Assad’s forces at the top of the hill, suggesting that these acts of digging and destruction were carried out under the supervision of regime forces (Figure 13).

7) Western Tombs

According to media reports and the local researcher Hassan Ali, who observed from the roof of his house, ISIS militants detonated numerous tombs in August 2015, particularly the tower tombs. Approximately ten tower tombs were destroyed, including the Tomb of Elabel and the Tomb of Atenatan, the latter being the oldest tower tomb dating back to 9 BCE. – Additionally, several house and underground tombs were also blown up. Field inspections revealed that these tombs have mostly been reduced to piles of rubble, except for a few that remain in relatively good condition and were not subjected to explosions. (Figure 14)

8) Northern Tombs

In 2017, a Russian base was established near the camel racing track in the area of the northern tombs. This involved levelling and clearing large areas to construct a military base and a helicopter landing pad, as well as fortifications for military points around the base. Additionally, the area was cleared to create earthen berms on both sides of the supply road connecting the base within the archaeological zone, linking all military units together. Currently, these sites have been vacated, and there is no military or civilian presence in the area. However, clandestine excavation activities have been observed inside the northern walls. (Figures No. 15, 16)

9. Museum of Popular Traditions (Tourist Information Canter)

The Museum of Popular Traditions is currently closed, but the building appears to be in good condition from the outside. (Figure No. 17)

- Recommendations and Proposals

- The Documented buildings and the rest of the archaeological city, spanning approximately 12 square kilometers including the oasis, require intensive efforts. A specialized team should be deployed to accurately document the current state, assess the extent of damage, evaluate the incurred losses, and re-document and register the remaining preserved architectural elements. The Palmyrene Voices team, in collaboration with the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, is capable of completing this task if adequate support is provided.

- The residential city requires a damage assessment and comprehensive rehabilitation of infrastructure and housing to enable residents—who form the third pillar of heritage alongside cultural and natural heritage—to return to their homes.

- The current situation demands urgent action from official authorities, humanitarian organizations, and civil society groups to meet the needs of these residents. This includes providing security forces to protect the city and organize resident affairs, teams to remove landmines and remnants of weapons, as well as access to water, food, healthcare, education, job opportunities, and financial aid (potentially in the form of supportive loans) to repair homes and encourage others to return to Palmyra.

- Syria’s political change and the victory of revolutionary forces following Assad’s fall on December 8, 2024, should prompt the new Syrian administration to reevaluate previous priorities and plans, particularly those involving joint projects with Russia. These projects appear to obscure Russian airstrikes’ role in destroying Palmyra’s cultural heritage. It is essential to seek more equitable local and international partnerships for rehabilitating and restoring the city.

- Ensure protection of Palmyra’s archaeological sites to prevent looting and vandalism.

- Authorities involved in restoring cultural heritage must also contribute to rebuilding the residential city to assist the local community in resettling in Palmyra.

- Develop laws and strategic plans that safeguard this heritage while criminalizing any harm or exploitation of it.

- Raise awareness among Palmyrenes about the value of their cultural heritage. Implement public policies aimed at highlighting the role that both tangible and intangible cultural heritage play in society. Integrate its preservation into planning programs for decision-makers while enhancing opportunities for its sustainability.

- Involve the local community in decision-making processes that will determine Palmyra’s future. Sponsoring entities must consider their perspectives on how to restore their heritage while encouraging displaced residents to return so they can actively protect their legacy.